Parents and students are attracted to 3-year bachelor degrees, but can institutions make the business model work?

September 23, 2025 BlogDifferentiation is going to be critical for colleges and universities to compete, and more than 60 are now…

More times than we can count, we have heard university leaders say, “We don’t want to build a strategic plan that just sits on the shelf.” This sentiment underscores what has been a perennial weakness to the strategic planning process – lots of work goes into producing a document that contains aspirational statements and goals that are static and do not reflect the dynamic environment in which institutions operate. Acknowledging this, we’ve been working with institutions using a nimbler planning process and tools that support active and dynamic decision-making and financial sustainability.

This month, we cover three key best practices to developing actionable institutional strategic plans as informed by our higher education team’s recent experience partnering with institutions on strategic planning efforts.

Here are a few things we are learning… Below, we cover three key best practices to developing actionable institutional strategic plans as informed by our higher education team’s recent experience partnering with institutions on strategic planning efforts.

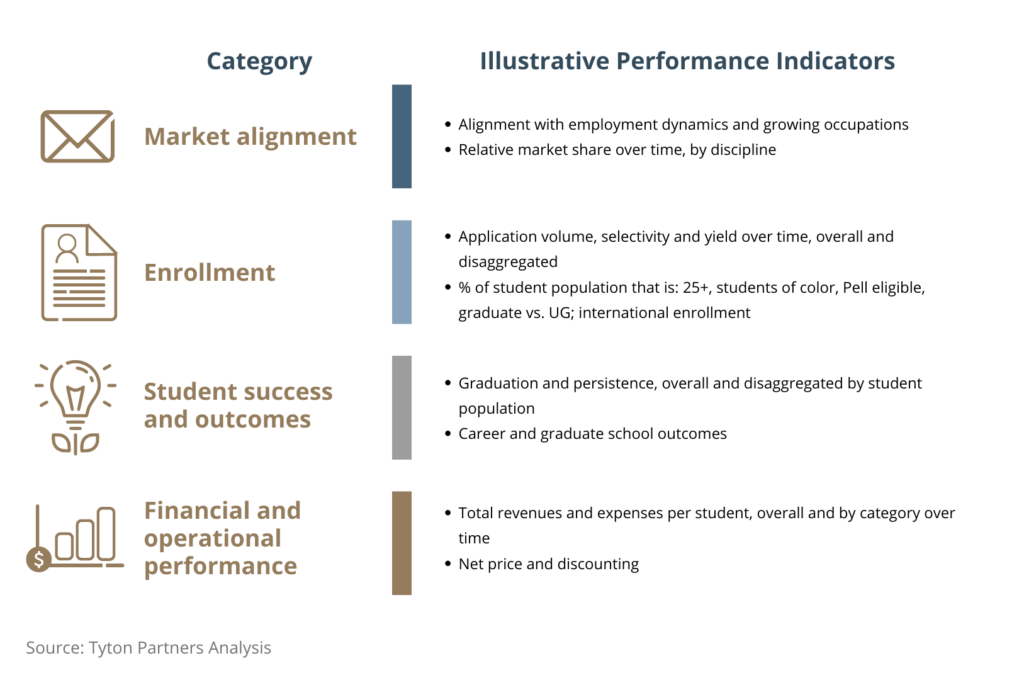

Any strategy development process requires institutional leaders, board members, faculty, and staff to have a collective understanding of the position and state of the institution in context of market dynamics. This analysis is about understanding key performance indicators and using those to identify areas of strength, challenge, and opportunity for improvement. Done effectively, it sets the stage for envisioning alternative futures for the institution based on market realities and places where institutions are out- or under-performing today. This “outside-in” analysis often challenges assumptions, leads to some critical moments of self-discovery, and identifies areas that require immediate focus.

Four key categories and illustrative elements that are among those we consider with our clients are shown below:

This exercise, in combination with reflection on the institutional mission and vision, helps to identify some of the key strategic levers that guide the institution, focusing leaders on the most essential elements for focus and consideration.

In traditional strategic planning processes, achieving consensus across stakeholders can dominate. This “don’t-rock-the-boat” approach builds a plan that satisfies stakeholders but may lack real direction and prioritization. In other words, institutions end up with a plan that includes “everything but the kitchen sink.” Forcing distillation of key decisions into levers that link to key financial outcomes in support of institutional mission forces leaders to focus on the most important decision points. Additionally, this exercise builds the strategic decision-making muscles of leaders that are critical to actively managing these decisions moving forward.

For example, the strategic levers that drive significant student success and financial outcomes at an undergraduate-oriented residential institution include the undergraduate portfolio and experience, the application of equitable student support infrastructure, and how real estate investments are managed in service of achieving this experience, among others. At an institution that has significant online programs or auxiliary service activities, for example, these levers would look quite different.

We acknowledge that the development of a strategic plan document is important as an internal and external marketing tool, as it publicly shares the institution’s mission, values, and key priority areas. However, implementation requires the ability to actively adjust to dynamic external and internal conditions. Flexible models support real time adjustments to modify strategy given these changes.

For example, one scenario might have an institution expanding significantly into a discipline cluster as part of an institutional priority to align to regional labor force needs with significant employer support; another may lead to increased diversification across disciplines in response to a changed labor market or unexpected event. These tools are helpful to apply during strategy development to ensure that strategic choices are being made about where to make “bets” as well as on an ongoing basis to ensure those bets remain calibrated to changing realities.