K-12 Predictions for 2026

December 18, 2025 BlogThe K-12 market has entered a period of structural change, driven not by a single shock, but the…

Our last impact article discussed the delicate balancing act between trust and evidence. In this follow-up piece, we’ll discuss some approaches and frameworks which can help philanthropists and impact investors manage and formalize their definition of “what is enough evidence for me to be satisfied I’m making the right choice?”

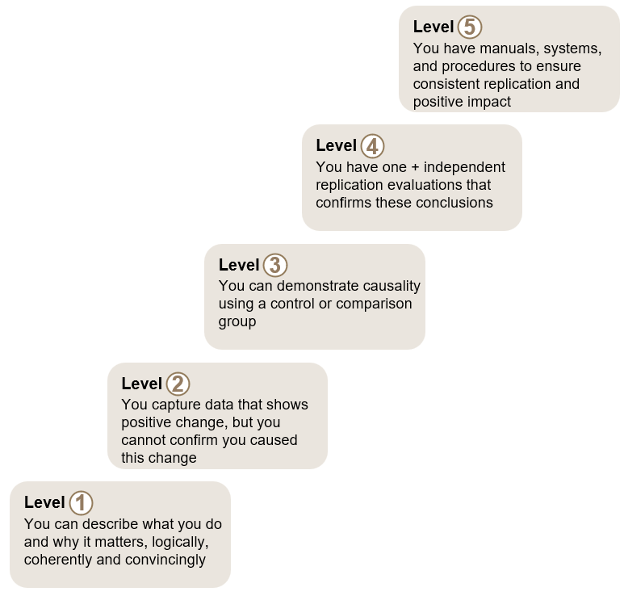

The tool we use most frequently in our work is the U.K. foundation Nesta’s standards of evidence framework. Their whole approach to impact investing is well worth reading, and this is a particularly flexible and transferable element of it. It provides a clear way of identifying what you want for different levels and types of interventions and applies to all fields:

The U.S. Department of Education’s ESSA tiers of evidence are similar to Nesta’s, with further detail relevant to K-12 materials in the United States. As many readers will know, funding has been tied to the ESSA standards, giving them real importance.

Here at Tyton, we have used this framework in both philanthropic and impact investing contexts. For example, it is a component of our work on the Cambiar THRIVE grant in the U.S. around family engagement, where we have provided it to grantees to help them think about their own stage of development; and, here in Europe, it is a key element of the new Creas Impacto fund’s investment criteria, where different standards of impact evidence are required for different stages of a business (e.g., Seed vs. Series A).

No framework solves every issue. Challenges emerge towards the more rigorous end of the evidence spectrum. In healthcare, large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard of evidence. This approach is taken in education, notably in ESSA Tier 1 and by the English Education Endowment Foundation and UK National Foundation for Education Research.

However, there is some debate about “the challenge of context” in education – can you safely generalize between different classrooms with very different students and very different teachers in very different cultural contexts? Even if you accept that randomization mitigates this problem, we now face an even more significant challenge to the RCT: the pace of change. The large amount of time (and money) required to effectively carry out an RCT in education has made it somewhat prohibitive in most contexts. With the rise of artificial intelligence and the corresponding acceleration of change, the shortcomings of RCT are even more stark.

The hottest area of education innovation right now, large language model artificial intelligence (LLM) applications, is changing so fast that we think it is impossible to stand up and run RCTs that look at LLM AI tools. By the time you have even got the study through all the necessary approvals, let alone started, there will be a new version of the technology (we’re currently experimenting with Chat GPT 4o, released in the last few weeks, and part of more-than-monthly feature improvements to this tool alone).

Should we evolve our use of frameworks such as Nesta’s to adapt to a more rapidly evolving ecosystem? Do we need to learn to accept a lower level of certainty to be able to evaluate the myriad of products and features that spring up every month? Is the only way to understand the efficacy of AI to use AI itself?

If you are evaluating traditional education solutions, or are braving the new frontier of AI in education and have an innovative way of gathering and assessing “what works,” we’d look forward to hearing from you and sharing it more widely with the field. Never has it been more important to separate the rhetoric from the messy reality!

In case you missed it, we encourage you to check out part one of our series on Evidence and Standards of Evidence.