The Swerve: K-12’s Age of Transformation

October 22, 2024 BlogOne of the most memorable books I taught as a World History teacher was Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve….

Partnerships are on most institutional leaders’ minds these days – whether they are approaching them with an eye towards innovation, expansion, or sustainability. The upsides are enormous, and more often than not, far outweigh risks. We’ve been working with clients quite a bit this year on partnership strategies to support their goals of expanding offerings, opening new marketing channels, and managing expenses through shared services and shared risk designed to strengthen and support the durability of the institutional mission. Below we share tips to embed your partnership strategy into the mindset of your organization and to maximize its impact.

Partnerships take myriad forms and support different goals, but institutions frequently bundle them together as a combined strategy that sits apart from the day-to-day work of academic and operational leaders. While it’s common and frequently effective to have a single leader dedicated to shepherding partnerships, care should be taken to ensure that all leaders “own it” and view it as part of their core job. Partnerships shouldn’t be relegated to strategic planning exercises alone, but rather, integrated into weekly cabinet meetings and job descriptions.

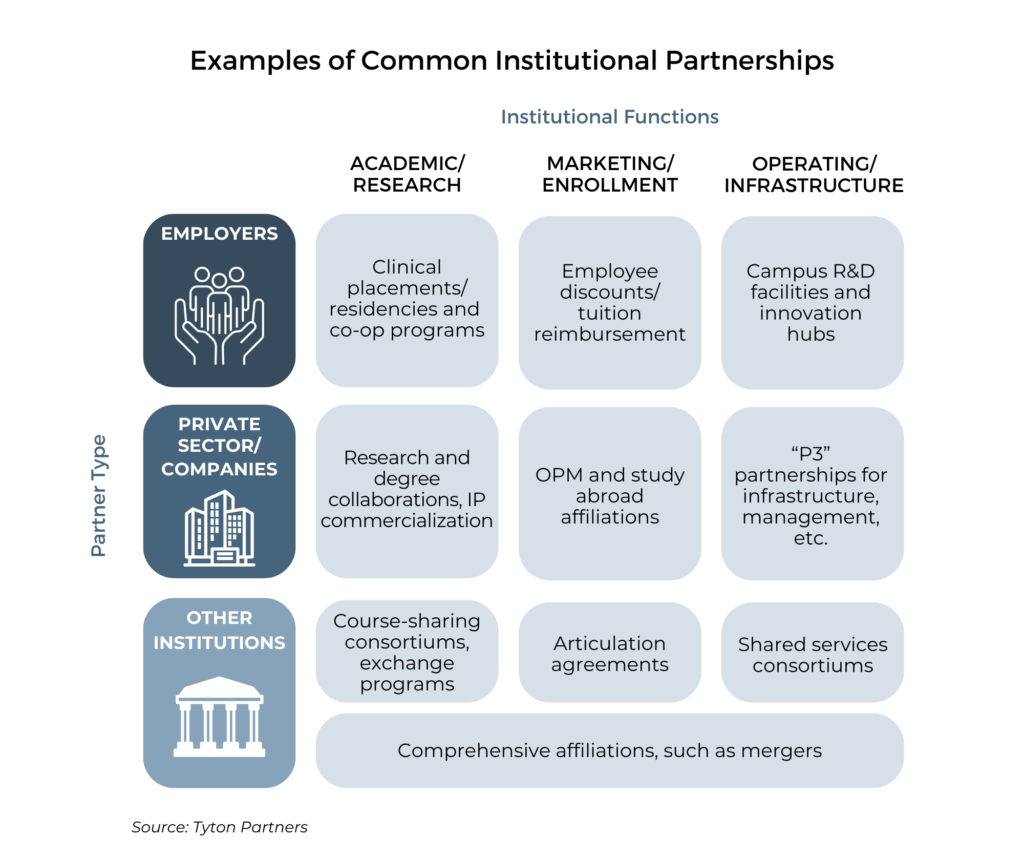

Leadership teams should align on the specific types of partnerships that best support your goals, risk tolerance, and mission, and then triage your focus and effort accordingly. The graphic below provides examples of partnerships across different partner-types and across institutional functions. They range from rather ubiquitous and lower risk/lower reward affiliations such as articulation agreements between institutions, to high stakes “P3” partnerships and institutional mergers. Given the differences in the purpose and the design of each kind of partnership, it’s inadequate to think, talk about, and plan for them generically.

Institutions have become more savvy to the benefit of hiring partnership leaders with traditional business development skills and experience, who are able to initiate relationships and “close deals.” But as the graphic illustrates, it would be almost impossible to find one person with the subject matter expertise to fully represent your institution across all of these. Whether or not you have a designated partnership leader, you should be deliberate in creating teams – most of which will be small in number and temporary in duration – to initiate and diligence new affiliations. For instance, if you are heavily focused on academic partnerships via consortium agreements, assign faculty with specific program-level experience and the imprimatur of the deans and/or provost. Alternately, if your partnership goal is a transformative merger with another institution, you will need someone who is known to have the ear of the President and who has the authority to leverage senior cabinet members as necessary, along with outside advisors such as banking advisors and legal counsel.

Partnership strategies too often fail to contemplate the actual implementation, as evidenced by the thousands of MOUs lost in file systems and the many conversations that start with “Whatever happened with x…” As with the initial “get,” the implementation strategy should be tailored and resourced, and it should be institutionalized so that it can weather staff and faculty turnover.

If increasing employer partnerships is your strategy, don’t expect the pop-up team that establishes it to also then manage the many new relationships; they need to move on to nurturing new ones. Success here will require specialist(s) to own the ongoing relationships at the employer including setting up marketing events, working with individual employees to navigate the program application process, and figuring out ways to grow the partnership. At one institution that used this strategy, ~20% of new graduate student starts resulted from this hand-off strategy after just a couple of years.

Another example of the hand-off occurs when institutions merge. Once the negotiating team and outside advisers complete the transaction, dedicated teams of operators with resources and expertise must then grab the baton and do the hard work of developing reorganization and integration plans across combined functions, consolidating workflows and technology, and establishing new sets of KPIs.

Partnerships individually and taken together can have a meaningful impact on your institution’s offerings and operations, and as such, there is risk in delay. It’s best to initiate partnerships of all types from a relative position of strength, which is to say, when your enrollment and revenue reflect a healthy and sustainable institution. This will alleviate the risk a partner may feel of investing time, effort, and brand association in an institution that won’t have the resources and focus to make the partnership successful.

We described the importance of urgency and deliberate action in regard to institutional mergers last year in Avoiding the Trap of Too Little Too Late. Much of his advice applies broadly to all types of partnerships, including: “There will always be voices that believe the decision is premature. But if the need to [partner] is obvious, chances are good the decision is being made too late to be effective.”

Best of luck with your partnership strategy moving forward, and don’t hesitate to contact us here if we can be of assistance as you think through your options and approach. We’ll also be continuing our webinars and virtual salons on the higher education space, so please don’t hesitate to reach out if you’re interested.