Catalytic Capital: From Recognition to Action in Education-to-Workforce Investing

July 8, 2025 BlogThe education-to-workforce pipeline is under pressure – and changing fast. The World Economic Forum notes that employers around…

Across the last few years, the market for instruction materials in higher education has undergone a realignment of epic proportions. Widespread outrage over materials costs has caused publishers to introduce new, lower pricing models, led professors to explore free resources, sometimes funded by philanthropic projects, and forced many students to forgo textbooks altogether.

The net result has been a decline in average student spending on instructional materials. You can therefore imagine my surprise when my daughter presented me with a receipt for her used developmental psych textbook: $180 bucks.

Gates Bryant

The ultimate outcome of the current upheaval in the market for instructional materials remains unclear. Ownership of the major publishers and distributors has changed, college bookstore revenues have plummeted, and students have seen prices decline for some purchase options, but increase for others. Subscription models looking to mimic the Netflix all-you-can-eat model have been launched by publishers and distributors alike. Textbook alternatives from open educational resource providers have become an increasingly popular option. And, college students, among the most value-focused consumers on the planet, have exploited every arbitrage in their search for the best deal.

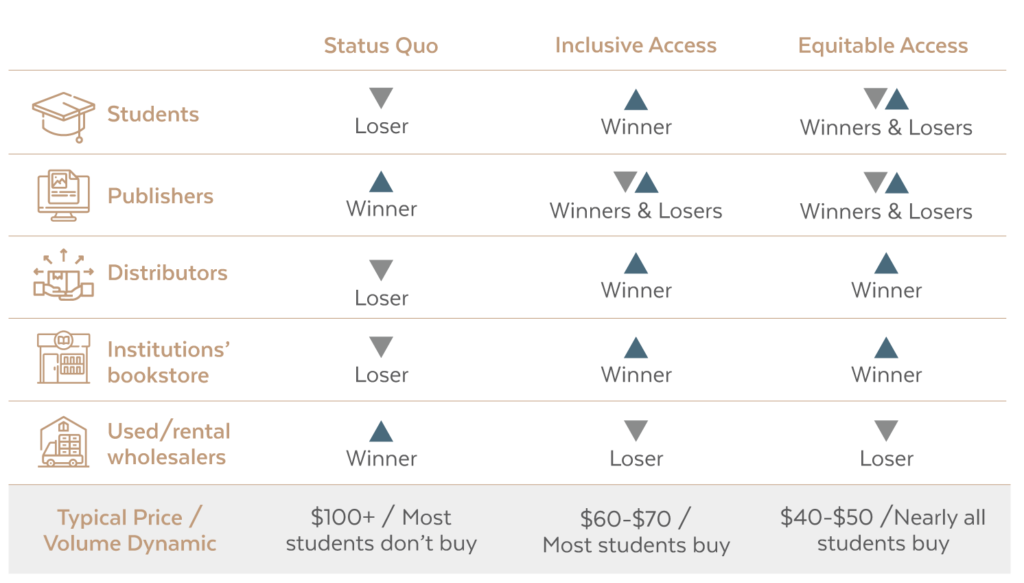

So where are the best deals and who will be the winners and losers as this realignment convulses through the stakeholders in the higher education ecosystem? The answer depends on how institutions choose to adopt and procure instructional materials in the future. Today, schools are facing three broad options: status quo, inclusive access or equitable access. In the status quo model, faculty and department chairs select required course materials, bookstores offer the title across a variety of formats and purchase options and students find the best deal or they don’t purchase at all. In Inclusive access, bookstores partner with distributors to offer students the required materials at a lower overall price, generally in digital format; the lower price is negotiated with publishers on the expectation of higher volume or “sell-through” and students must opt-out of the program if they prefer another option. Equitable access, which provides access to all materials across all courses for all students for one cost per student per term or credit hour, is a more recent access model but is being adopted by a growing number of institutions.

Despite vociferous debate from different camps, all three options can and do preserve the faculty’s right to select materials and students’ right to opt-out of the materials required for their courses. Based on our study Time for Class 2021, 20% of survey respondents reported offering inclusive access at their institution and the share of students having access to materials on the first of day of the course increased 3-5x when inclusive access is in place. At the moment, adoption of inclusive access models appears to be growing while status quo is slowly in decline. Equitable Access (EA) is too new to judge but could either hasten the decline of Status Quo or split the share of institutions inclined toward new models at the expense of Inclusive Access (IA).

Given the steady shift to these new access models, why would we see $180 for a used textbook? It’s really a question of economics for those in the market. The used book wholesalers and college bookstores that retail the used books are holding on to a revenue stream that is in rapid decline, so they’re preserving revenue by keeping the price as high as possible. At the same time, at institutions that offer IA, volumes are up as fewer students opt-out. For the publishers with expansive catalogs and a strong presence in high enrollment course IA and EA can be accretive. Across this evolution, we see students having generally the most to gain so long as they’re provided with the transparency to opt-out: they gain access to the learning materials they need at a lower overall cost. Below we offer our view of the winners and losers as this shift plays out at institutions across the sector. However, we also acknowledge that this is a complex shift playing out over time; we haven’t, in this short piece, addressed the incredible variability in prices across disciplines and courses, or, the ongoing impact of OER or direct-to-student subscription models. With all of this complexity, perhaps we should conclude then that the revolution is here and picking up momentum.

What are your predictions?