Behind the scenes of Otterbein University’s partnership with Antioch University

June 10, 2025 BlogWe’re excited to launch Tyton Partners’ new interview series, Five for the Future: Spotlight on Transformative Institutional Partnerships….

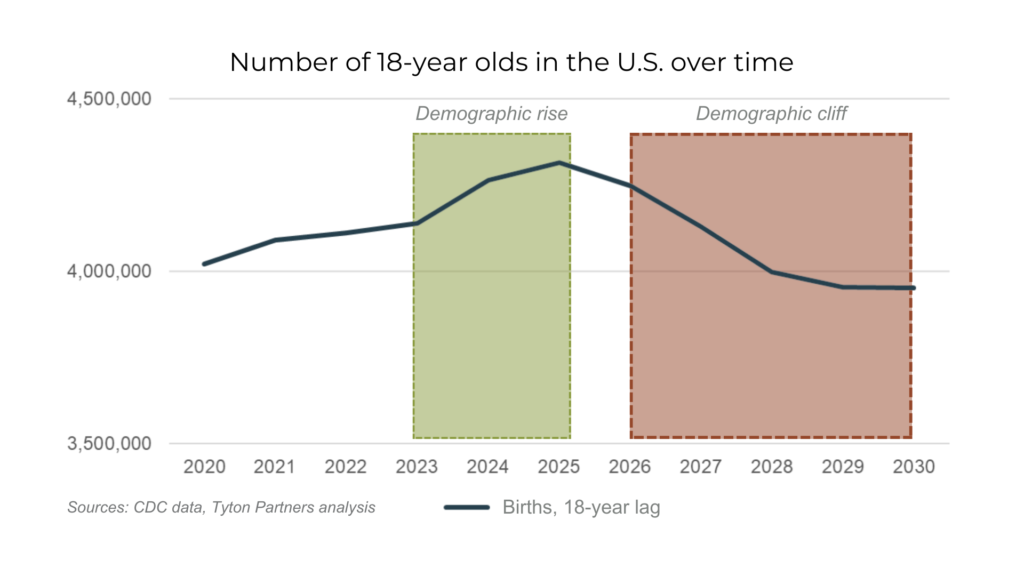

“Looming Enrollment Cliff Poses Serious Threat to Colleges” … “Will Your College Survive the Demographic Cliff?” … “The incredible shrinking future of college” … While the impending “Demographic Cliff” — a decline in the number of traditionally college-aged people projected to impact the 2026 academic year and beyond — has been headline news in the Higher Ed space throughout recent memory, it is essential to recognize that enrollment dynamics are shaped by a multitude of variables, with some sinking, and others buoying, college enrollment.

At the ASU-GSV conference earlier this spring, we facilitated a conversation about enrollment among a diverse set of panelists. With this esteemed group, we collectively agreed to round out the “cliff” motif, with an “escalator” as a more appropriate metaphor to capture the ups AND downs of enrollment in higher education over the next several years. While we will be faced with a declining traditional-college-aged population, a convergence of other factors — the softening job market, a rise in online learning, potential increased federal tuition assistance, and rebounding international student enrollment — all work together to provide a less dire picture of overall enrollment across the higher education sector for those institutions that position themselves appropriately.

While the Demographic Cliff looms large on the horizon for many institutions, its real story is not one of linear drop-off. To summarize the Demographic Cliff in a nutshell, there was a sharp decline in births during the Great Recession (approximately -3% YoY growth from 2007-10 in the U.S.), with birth rates not fully recovering to pre-Recession levels; those born during that period are nearing 18, the traditional age for first-year students.

While the eventual Demographic Cliff will prove to be a headwind in the years to come, demographic adjustments have a variable impact on enrollment depending on which way births trended 18 years prior. Less often discussed than the Cliff is the “Demographic Rise”: a ~2% YoY increase in births from 2003–07, which will increase — and already has increased — the potential supply of first-year students from AY ’21 through AY ’25. In AY ’23 – ’25, we should see an increase in enrollment — or at least the supply of potential enrollees, as the college-going rate may vary — due to the Demographic Rise; thereafter, declining birth rates will contribute to supply downturn beginning in AY ’26. It is important to note that the scenario of potential supply impacting enrollment only plays out when the college-going rate is similar. We expect that this rate may slightly increase in the years to come, validating the idea of the Demographic Rise and dampening the impact of the Cliff.

With all of this in mind, it’s important to note that AY ’26 is the start of a demographic decline, not a doomsday event. With the time it will take beyond 2026 for smaller high school classes to matriculate through enrollment years, the Demographic Cliff is less imposing within a 5-year outlook than the headlines might suggest, and not a major factor within the next ~10 years for graduate enrollment.

The signal power of a postsecondary degree is still there, despite a rise in alternative credentials. In recent years, as recessions have hit, the number of jobs available to those without a college degree has declined, while the number available to those with them has remained largely flat. Moreover, historically, the job market has had a significant correlation with college enrollment — higher education is famously countercyclical, with more students opting to wait things out in college during recessions, and opting to get a job straight out of high school when the market is hot.

Economists, including those we interviewed to validate our enrollment analysis, anticipate a recession and fewer jobs available within the next two to five years. As a result, we expect to see more students go back to school as immediate job and financial prospects grow muted.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the growth of online learning seen in the decade prior to it. While most pandemic-era digital learning experiences were temporary, impacts are lasting — many institutions that were forced to rapidly digitize due to COVID-19 have kept online/hybrid options and/or launched new online programs. Student interest has increased alongside, with 95% of surveyed online students reporting their experience as “positive” or “very positive”, as compared to 86% pre-pandemic, based on data from Wiley’s Voice of the Online Learner 2022 report; our forthcoming Time for Class survey report of over 2,000 students shows that almost ¾ of students report if they could choose just one way to take class, they prefer online, hybrid, or blended format over face-to-face. Given this hike in interest, growth in availability, and heightened participation, we expect to see a continued increase in the share of students opting to learn online.

Online learning directionally provides students with greater optionality and accessibility, and the increases in students’ interest in participation have been rapid. However, limited longitudinal data exists — given online learning’s relative newness — to conclusively demonstrate whether online expansion leads to increased overall enrollment or just more students opting to learn in that modality. As more data becomes available, Tyton will continue to hone in on how many students are choosing to learn online that would not otherwise have enrolled in Higher Ed.

While federal tuition assistance policies hold potential for enhancing access to higher education, their impact on enrollment is expected to remain flat for the time being. President Biden’s promise to double the maximum Pell Grant award faces challenges given the current political landscape (instead increasing by $500 in the latest federal spending bill), and free community college initiatives are not expected to drive robust enrollment growth in the near term given their state-by-state scope and their traditional exclusion of other expenses, such as textbooks, housing, and other living expenses. With the maximum Pell award covering less than a quarter of the average cost of attendance across all institutions as of NCES’ most recent institutional data update (2021-22 academic year), federal tuition assistance would have to notably change to move the needle on enrollment. Though no one can with full confidence predict policy changes, given past changes and current legislative dynamics, a meaningful shift is unlikely. That said, if significant changes were to occur, it would likely result in major enrollment swings, making federal assistance changes an unlikely wildcard factor vis-à-vis enrollment.

International student enrollment is a significant contributor to certain higher education institutions’ revenue and campus diversity. Recent geopolitical uncertainties, visa restrictions, and the lingering impact of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted that for some, with a 15% YoY decline from Fall 2019 to Fall 2021. However, international enrollment is showing signs of recovery: from 2021 to 2022, undergraduate international enrollment was up 5% YoY, graduate by 26%. While some of this growth is a rebounding effect, when balancing pre- and post-COVID years, moderate to high continued growth is anticipated.

In 2022, there were a total of ~1M international students enrolled in U.S. higher education, accounting for ~5.5% of all enrollment. Although international enrollment is a relatively small share as compared to total, its growth provides a solid buffer against demographic downturn: bearing in mind geopolitical uncertainties, Tyton projects heightened international enrollment in U.S. institutions, which may offset up to 25% of all demographic-induced enrollment decline in the years where the impact of the Cliff picks up.

Note: 25% cited refers to Tyton’s projection for the 2028 academic year, two years into the “Demographic Cliff”, the first year where an enrollment downturn is projected

While macro-level pushes and pulls exist in the enrollment picture, institutions and their various strategic support networks can have a hand in shaping enrollment outlooks themselves. In particular, to address enrollment challenges, stakeholders can:

Colleges should optimize their recruitment strategies and improve their outreach efforts to attract a diverse pool of prospective students. This includes enhancing marketing campaigns, strengthening relationships with feeder schools, and utilizing technology to streamline the application process. With fewer 18-year-olds available, institutions should emphasize targeting potential adult learners in particular, a cohort that will not be impacted in size by any coming demographic shifts. With the prospect of a forthcoming Supreme Court ruling against affirmative action in college admissions, the methods, practices, and technology services that institutions have relied on for the last decade or more are poised for a major redesign.

Institutions can implement policies and programs that increase accessibility for underrepresented populations, such as students and students from marginalized communities. This may involve expanding financial aid opportunities, providing academic support services, and creating a welcoming campus environment that embraces diversity and inclusion.

Colleges should prioritize student success and retention by implementing comprehensive support systems. This includes academic advising, mentoring programs, tutoring services, and mental health resources. By providing the necessary support, colleges can enhance students’ sense of belonging, persistence, and degree completion rates. If demographic shifts will result in a lower supply, ensuring the retention of those students is not only critical for student achievement, but for institutions’ enrollment bottom-lines.

Although we may not see the dip in enrollment that some are expecting, even modest declines may add financial pressure to institutions on top of what many are already facing due to high fixed costs, student debt aversion, high competition, and a variety of other complications. In addition to the efforts listed above, institutions may need to partner/affiliate to support efficiency and scale, refine their strategic priorities, align their program portfolios with market demand, and potentially make pivots towards online optionality. Whether the escalator is heading up or down, getting handrails in place to guide the path forward is imperative.