What We’re Thinking About in Impact for 2026

January 21, 2026 BlogThe education sector is navigating a fundamental shift. Market forces are driving consolidation, capital is more selective, and…

Across the last two decades, every content-driven industry in our economy, from music to movies to books to legal information, has undergone distribution revolutions. These revolutions have driven prices down and increased competition thanks to the new business models and pricing strategies they have catalyzed. Instructional materials in higher education have been among the slowest to change until recently. So, let’s revisit and update our post from two years ago.

On January 11th, 2024, the U.S. Department Of Education proposed “cash management” regulations to prohibit institutions from charging students for assigned instructional materials on their tuition bills with few exceptions. The proposed regulation would significantly impede the growing support and adoption of Inclusive and Equitable Access models for instructional materials, which offer course materials at a discounted fee per course or term/credit hour, generally delivered digitally, and added automatically to their tuition bills. These models were intended to be a critical enabler of the textbook revolution, driving down costs and dramatically increasing day 1 access to materials for students. It turns out the revolution may be thwarted at the gates.

This month, we revisit a post from 2022 where we continue to articulate the winners and losers in the move toward Inclusive/Equitable Access models. We also will share some of our findings from Time for Class 2023 which demonstrate growing support for these models from higher education administrators, faculty, and students since then.

The DOE claims its proposal to impede these models will promote affordability and protect student choice. However, while there is room to improve these models and the higher education community is still in the early stages of understanding how best to implement them, the Department offers no alternative to restricting them entirely. We are scratching our heads as we see these models as one of the more promising elements of the textbook revolution we were all promised.

The market for instruction materials in higher education has undergone a realignment of epic proportions. Widespread outrage over materials costs has caused publishers to introduce new, lower pricing models, led professors to explore free resources, sometimes funded by philanthropic projects, and forced many students to forgo textbooks altogether.

The net result has been a decline in average student spending on instructional materials. So, you can imagine my surprise when my daughter presented me with a receipt for her used developmental psych textbook: $180 bucks.

The ultimate outcome of the current upheaval in the market for instructional materials remains unclear. Ownership of the major publishers and distributors has changed, college bookstore revenues have plummeted, and students have seen prices decline for some purchase options but increase for others. Subscription models looking to mimic the Netflix all-you-can-eat model have been launched by publishers and distributors alike. Textbook alternatives from open education resource providers have become an increasingly popular option. And college students (among the most value-focused consumers on the planet) have exploited every arbitrage in their search for the best deal.

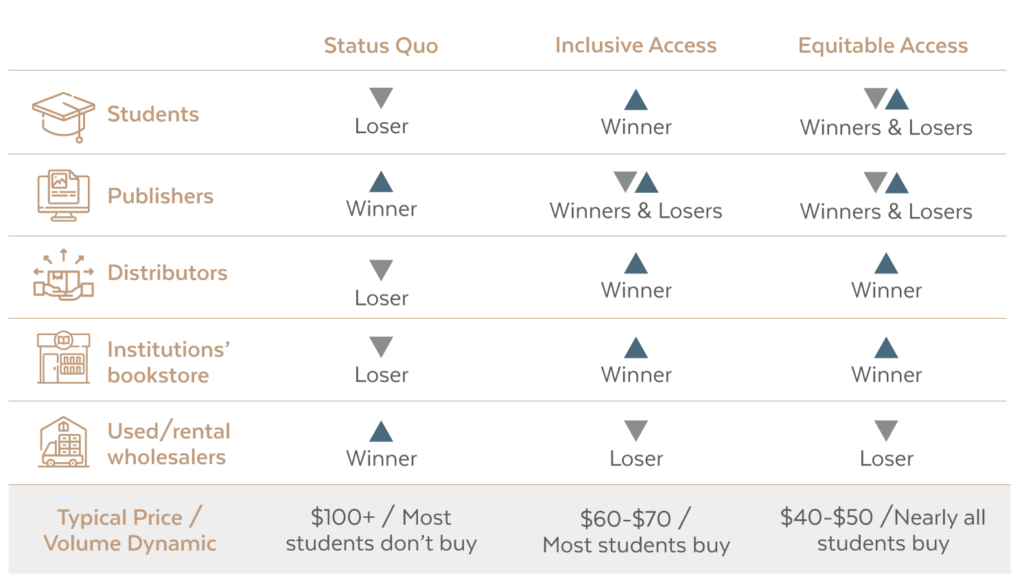

So, where are the best deals and who will be the winners and losers as this realignment convulses through the stakeholders in the higher education ecosystem? The answer depends on how institutions choose to adopt and procure instructional materials in the future. Today, colleges face three broad options:

In the Status Quo model, faculty and department chairs select required course materials (that are either for purchase or free), bookstores offer the title across a variety of formats and purchase options, and students find the best deal, or they don’t purchase at all.

In Inclusive Access, institutions partner with distributors to offer students the required materials at a lower overall price, generally in digital format; the lower price is negotiated with publishers on the expectation of higher volume or “sell-through” and students must opt out of the program if they prefer another method of acquiring the required materials

Equitable Access, which provides access to all materials across all courses for a single fee per student per term or credit hour, is a more recent access model but is being adopted by a growing number of institutions.

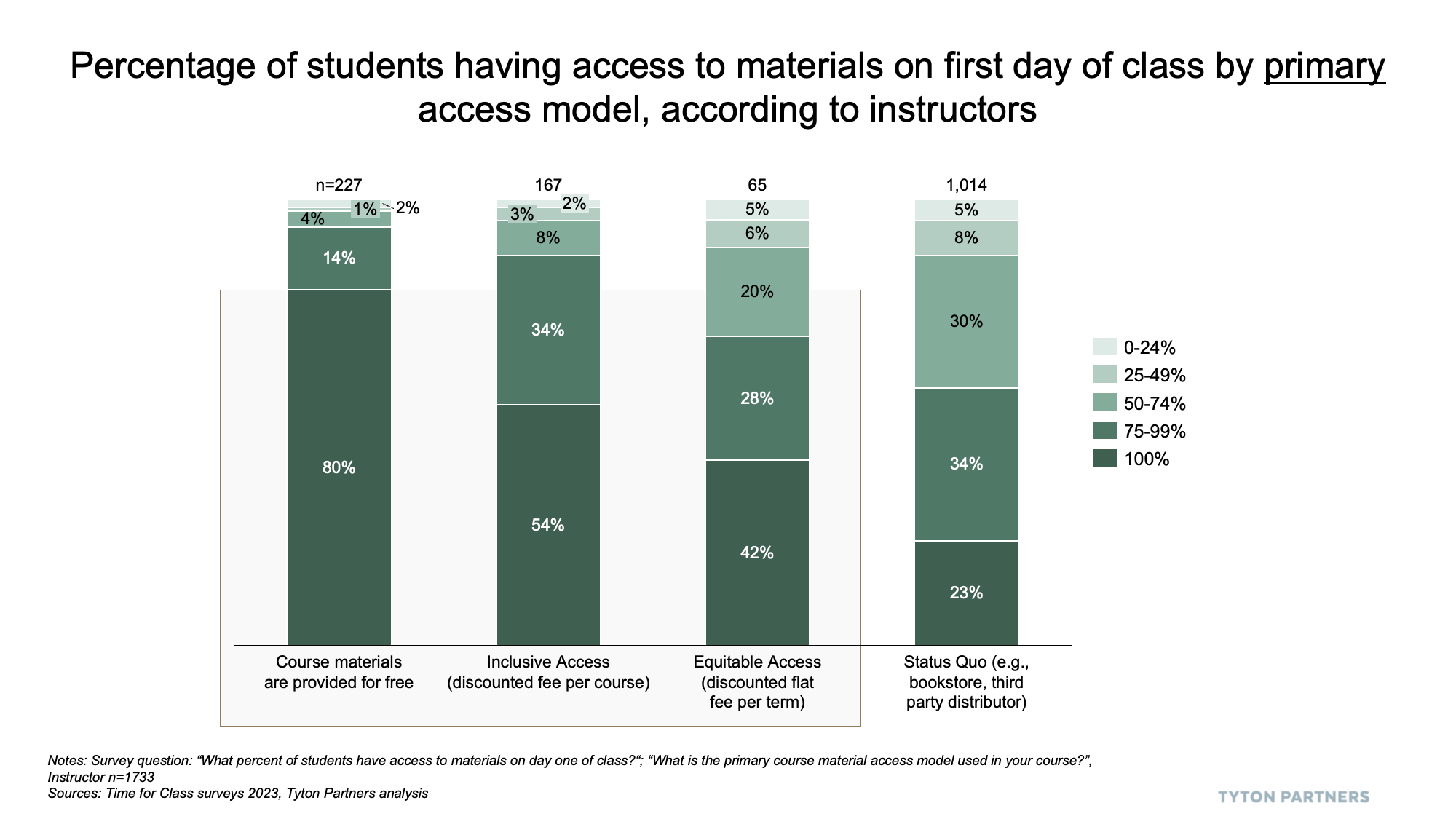

Despite what USDOE’s proposal insinuates, all three options can and do preserve the faculty’s right to select materials and students’ right to opt out of materials required for their courses. Based on our study, 22% of higher education administrator survey respondents reported offering Inclusive Access at their institution and the share of students having access to materials on the first day of the course more than doubled when Inclusive Access was in place. Over a quarter of administrators and faculty predicted an increase in the use of IA in the near term, so if USDOE’s proposal isn’t implemented, the adoption of Inclusive Access models will likely continue growing while the Status Quo model slowly declines. Equitable Access (EA) is too new to judge but could either hasten the decline of Status Quo or split the share of institutions inclined toward new models at the expense of Inclusive Access (IA).

What’s clear is that IA and EA models provide students with access to materials on the first day of class and that improves persistence and student success.

Given the steady shift to these new access models, why would we see $180 for a used textbook? My daughter’s school did not offer an Inclusive Access option, and the professor had selected an older edition with limited circulation. For the market in general, it’s really a question of economics. The used book wholesalers and college bookstores that retail the used books are holding on to a revenue stream that’s rapidly declining, so they’re preserving revenue by keeping the price as high as possible. At the same time, at institutions that offer IA, volumes are up as few students opt out of the program. For publishers with expansive catalogs and a strong presence in high-enrollment courses, IA and EA can be accretive. Across this evolution, we see students with the most to gain so long as they’re provided with the transparency to opt out: they gain access to the learning materials they need at a lower overall cost. Below, we offer our view of the winners and losers as this shift plays out at institutions across the sector.

We advise companies and institutions throughout the higher education sector on pricing strategy and see IA/EA as a potential critical enabler of the pricing revolution we’ve seen in other content-driven industries. The USDOE’s proposal impedes where many institutions and faculty see benefits and will slow down or stop the price declines that have finally started to accelerate.

Stay tuned for our next installment of Time for Class research on digital learning tools in May 2024 where, among other areas, we investigate the benefits and drawbacks of IA/EA directly through the lenses of HE administrators, faculty, and students. For additional questions, please reach out to us at info@tytonpartners.com.